These articles are aimed at senior management funding Software Developer or IT Professionals attempting to show the ROI benefits of what can sometimes seem counterintuitive.

This ever growing library is provided free of charge and can be found here.

In this article, part of my series explaining better ROI from software development, I look at Agile development.

What is Agile?

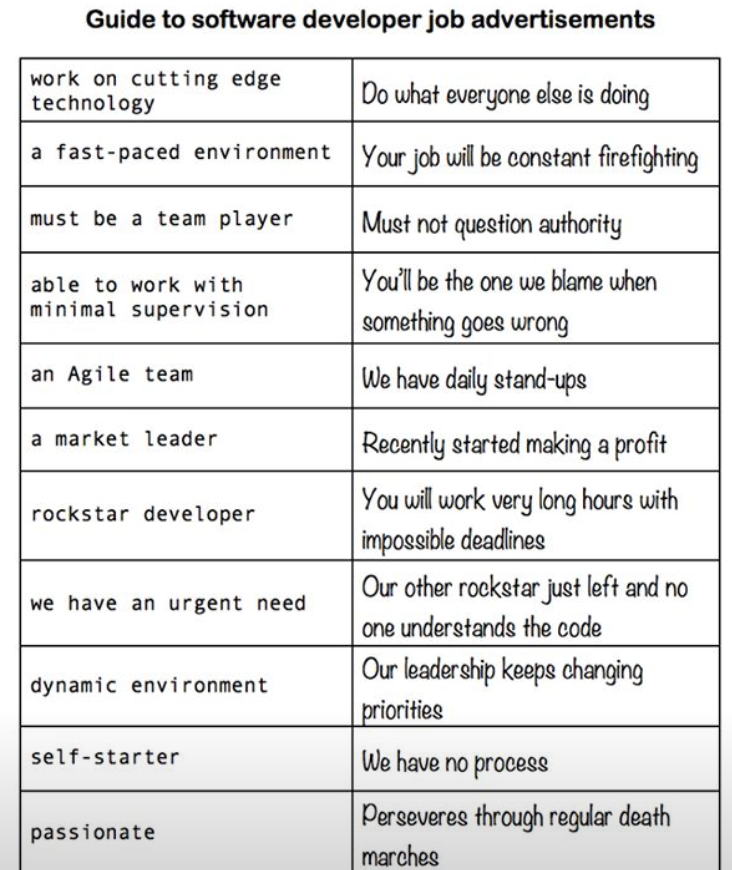

Agile is one of those words that has been used for a multiple of intentions within business and software development – mainly thanks to marketing departments or poorly informed managers.

I’ve even seen Agile being used as pseudonym for bad practice:

Source

Source

Agile, when understood and applied properly, however can be an exceptionally powerful mindset. In recent years we've seen it move out of software development into many product fields – including start ups. There is real value to be found if done correctly.

If you studied Lean or Radical Management techniques, then you’ll see a lot of similar principals.

What is Agile Software Development?

“Agile software development is a set of principles for software development in which requirements and solutions evolve through collaboration between self-organizing, cross-functional teams.” Wikipedia

For me, the best way to understand Agile is to review the Agile Manifest created in 2001 by some of software developments leading figures. A group that wanted to document underlying values they believed should be used in software development.

“At the core, I believe Agile Methodologists are really about "mushy" stuff - about delivering good products to customers by operating in an environment that does more than talk about "people as our most important asset" but actually "acts" as if people were the most important, and lose the word "asset".” Agile Manifesto

The Agile Manifesto

“We are uncovering better ways of developing

software by doing it and helping others do it.

Through this work we have come to value:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on

the right, we value the items on the left more.” Agile Manifesto

It is probably worth taking a few minutes to re-read the above. It’s important and shouldn't be skimmed.

The product of great minds

I'm sure you've heard the phrase “standing on the shoulders of giants”.

This relatively simple, yet hugely powerful, statement was the work of some very clever individuals – masters of their field – software development.

The first paragraph makes clear that they are still learning – but their combined experiences lead them to the rest of the statement.

This speaks to the maturity and continual discover with Software Development that I commented on in a previous article.

These experts have come to this statement by having lived the industry and learnt a better way.

Note that I don’t say “best” – maybe “best for right now” – but as the industry matures I would expect this to be superseded by even greater thinking.

Left Vs. Right

Those closing comments at the end of the statement are simple enough;

Those items on the left are (or in bold, dependant on LinkedIn formatting), in the expert’s opinion, of more value than those on the right.

In my reading, I take this to mean that even the items on the right are better than a complete absence. And it is the items on the right that I grew up with in my career.

I've never found them perfect, and we’ll touch on some of the shortfalls below, but good solid projects can be delivered using them.

Nowhere does the Agile Manifest say that the old ways can’t work. They can – we’ve all seen experiences of that. In general however, the Agile method produces better, more consistent, more cost effective results.

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

This is recognition that while there are value in process and tools, there can also be a fair amount of waste.

If you are familiar with Lean thinking or Value Stream analysis, then you will have come across the principals for splitting all the parts of a process into those that add value and those that don’t.

With development processes you will find they have built up around the central value of communication between 2 parties – the party requesting something and the party delivering something. Over time rules have been codified and levels of bureaucracy created – normally with the best of intentions – that can actual obscure the communication.

So in the past we've introduced Business Analysis, Project Managers, etc to frame the communication. And this can be useful – but it also means that the communication is going through multiple interpretations. This is not only time consuming (as well as people) but also a source of mistakes (chinese whispers ahoy).

The closer the interaction between the requester and the deliverer – the higher the chance of getting the correct thing in an efficient manner – lowering the cost of that delivery.

Working software over comprehensive documentation

This is in recognition that the whole point of software development is to deliver working, and in my option valuable, software.

Documentation is purely a by-product of producing that software. Thus you have to consider if it is actually adding any value.

This quickly links back to interactions or processes.

If your development process involved multiple levels with little direct interaction then there is huge value in documentation.

Good direct interaction however outweighs the need of comprehensive documentation.

Some documentation is useful – but certainly not the 100’s page specifications that I've seen previously. In most cases a few paragraphs setting out the high level intention is more than enough to act as a place holder until there is direct communication to fill in the gaps.

The working software should be what you are measuring your software developers against – not the quality of their documentation.

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Doesn't Customer Collaboration sound so much more fun and positive than Contract Negotiation?

The reason we spend so much time over Contract Negotiation is that we are trying to ensure that the balance of the scales are in our favour – we are getting more from it than the other party.

This is such a negative place to start from. We start in conflict.

Collaboration however is inherently a much better place to be in a relationship. If you have problems, you are working together to resolve it – much better than retiring to separate corners to pore over contract for who is correct.

Investing time and effort in delivery is always going to be a better ROI than ploughing it into defensive actions.

There will of course be times where you do need to have contracts in place. Just keep in mind that good relationships management is much better than having to rely on contracts. From experience, if you reach a situation where the contract is being cited then the relationships is likely already beyond repair.

Responding to change over following a plan

If there has ever been a truism within software development, it is that everything changes.

For years projects have failed because of an arrogance to believe that the plan was all important.

The plan is purely a method of getting from A to B. If B changes to C then the plan needs to change.

But with so much time and effort put into building plans and documentation, there has always been a reluctant to accept that change.

Look at the language – it’s a “Change Request”.

We have to request that change is accepted into the plan.

In fairness, there was good reason for this in most cases. Any change had so many knock on impacts – which, if nothing else, needed to communicated up the management tree.

The world however keeps spinning, opportunities change, more is discovered about how to exploit an opportunity – there are just so many good reasons for change.

“The only thing that is constant is change” Heraclitus

So while having a plan is great – being able to respond to that change is essential. Too many software project have suffered from an over emphasis on the plan – only to deliver the wrong thing.

“No battle plan survives contact with the enemy” Helmuth von Moltke

I believe we all know that plans are, at best, transient. Thus you have to question why we try to slavishly expect our subordinates to deliver them as originally drawn up.

Even our language looks for the team to justify why they are not to the plan – we start with a negative assumption that the team have failed and they have to justify why.

If we ignore the huge impact on morale – why spend the time (and cost) explaining something we already know is likely to change?

Trust

You may have read the above and started to think about how can I trust my development team?

All of those right hand items are there to make sure the development team are doing what I want them to?

Without them, what guarantee do I have that they will do what I need them to?

And of course trust is that core of this. As it motivation.

In my last article I talked about the three levels of drive described in Daniel Pink’s book Drive; the more you engage someone’s intrinsic motivators, the more they will push themselves. They want to do the best job possible.

This is where we hit a bit of a chicken and egg situation.

One of the key methods of establishing and encouraging Intrinsic Motivators is to have trust.

And it is so much easier to trust when you can see that team is driven by Intrinsic Motivators.

How does it start?

For me, it has to be with management. You have to create the correct environment for individuals and teams to establish that Intrinsic Motivators. By their very nature, you cannot force those motivators – they have to grow from the individual.

If you are in the fortunate position of having staff bubbling over with Intrinsic Motivators (some just naturally have it) then make sure you aren't restricting them. Make sure you are providing an environment in which your business is benefiting from that amazing force – and trust me it is an amazing thing to see in action.

In takes time

Sometimes there is the enthusiasm to jump into things with both feet.

If I've encouraged you to do that – then great. Just take it slowly.

We are talking cultural change here. This is something that doesn't (and shouldn't) happen overnight.

If you suddenly introduce this without signposting it to the team, then you may well scare them into thinking you have ulterior motives.

Also, don’t just pull up the drawbridge if things aren't transitioning quickly. This can be more negative that making the change in first place.

Luckily there is an easy way to handle it – talk to them.

When introducing any change; talk to them about why, what it is you are trying to do and ask for feedback. If they are reluctant, possibly step back, give them space to absorb then raise again.

If not working; describe to them why you feel it isn't working – again discuss it with them. Sometimes the most complex problem is solved through simple conversation.

But this is true of any change.

More Agile

I had originally planned on doing Agile in a single post. As it is, I've decided to carry this into a second article. In the second article I’ll look at the principles which form part of the Agile Manifesto.

If you wanted to read ahead, you can see that here.

Further reading

Agile Manifesto

• Statement • Principles • History

Drive by Daniel Pink