In this series of articles I am looking to outline why Scrum works for us. During the series I’ll be looking at the challenges in software development today, firstly in general and then specifically with two “traditional” approaches – waterfall and solo working. In the final part of the series I demonstrate how Scrum works for us to address those challenges.

I was motivated to produce these articles to educate our wider business. While we have been operating in a Scrum manner for over two years, acquisition has brought many new faces to the table – many of whom are confused by the way we are working. It’s also a great opportunity to refresh those that have been working with it for a while.

Introduction

This final article demonstrates how Scrum works for us to resolve the challenges raised in the first three articles. The previous three articles looked at development in general and two traditional development methodologies – waterfall and solo.

I’ll first summarise our Scrum process, then how we handle the challenges raised through this series of articles.

So what is Scrum

“Scrum is a simple framework for effective team collaboration on complex projects. Scrum provides a small set of rules that create just enough structure for teams to be able to focus their innovation on solving what might otherwise be an insurmountable challenge.” [Scrum.org]

For us, this is a series of rules what we follow to address the challenges identified in development. Scrum is not the only framework to address those challenges. It belongs to family of methodologies called Agile. All address the challenges to a lesser or greater extend. For us Scrum, or more importantly our version of Scrum, works for us.

Are we using Scrum?

A purist would answer no.

We are using what is lovingly referred to as “Scrum-but” – we use Scrum but we do this differently because …

There are a few example of “Scrum-but” in our process – which I’ll highlight as we go through.

While it doesn’t strictly follow Scrum guidelines – I personally believe that we still achieve the principles (and thus many of the benefits) within Scrum.

Part of Scrum is to iteratively review and adaption of the process – thus at some point we may review and remove the “Scrum-but”s.

2 week Sprint cycle

We break our development time up into 2 week cycles. These are defined within Scrum as “sprints”.

By breaking up development into short “sprints”, it allows a business to ensure that the development team are always working on the most important tasks at any given time.

Our process focuses on how the business chooses what is important (prioritisation), what the development team believe will fit within a two week sprint (estimations) and then the actual development.

Trello cards (http://trello.com)

We use a number of tools to assist us with our Scrum process. Primary amongst these is Trello.

We use Trello to provide a visual representation of our Scrum process. We use an online system so that it’s visible to both internal and external stakeholders.

Trello provides us with transparency so that anyone within the organisation is able to see what we are working on, what we’ve done and what we have left to do.

Trello provides us with “cards” to describe what is to be developed and columns to tell us where the cards is within the process.

Trello cards provide a brief description of the development task being requested. The card should only document enough to remind the team what the development is – the primary purpose is to prompts further conversation (generally during the development). It is important not to fall into the trap of producing a requirements document by another name (see the second article).

As the card is moved through the process, we move them through the following columns in Trello:

- Next Sprint

- Current Sprint

- Dev

- Test

- Review

- Done

All cards move between the columns in parallel with the actual work.

Prioritization

We run a fortnightly meeting to, as a team, prioritise our Trello cards into a business priority.

This is a “scrum-but”. Scrum describes as specific role – Product Owner who would be responsible for deciding on the priority.

Our process allows for the entire team to bring cards to the table, summarise their business value and then finally vote (as a team) to produce an ordered list.

Personally I’ve found this incredibly empowering – both in terms of an open door policy for anyone to propose an idea but also then everyone having equal rights to vote on the priority – be they MD or Warehouse worker.

Estimations

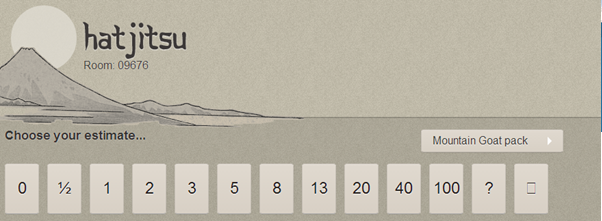

Once we have our prioritised list of cards, then the development team will estimate them using a system called planning poker.

They will discuss the cards, in priority order, and each provide a blind estimate of how long the card would take in “perfect developer days”. “Perfect developer days” is a fictional day where a developer would have no distraction and would be able focus on just working on the problem at hand.

The estimate will be based on a sequence of numbers that becomes wider spaces as they grow. This is a great reflection of how inaccurate an estimate can be as the task becomes larger.

For this we use hatjitsu (http://hat.jit.su) which allows for the blind vote:

The principle being that each developer, after discussing the card and asking any questions, would make their own estimate.

In the event of consensus across the team, then that estimate becomes the card estimate. Should there be a difference of opinion then they are discussed and the team are asked to come to a consensus.

This opportunity to disagree and then reach consensus is incredibly important.

Firstly, it allows the team to highlight any differences in understanding between individuals. This has certainly picked up instances where an individual has either completely underestimated the work needed or over complicated it – generally through misunderstanding.

Secondly, it prompts buy-in from the team. In the book “The Five Dysfunctions of a team”, Patrick Lencioni promotes conflict situation (within a safe environment) to ensure that everyone’s voice is heard. He notes that an individual doesn’t have to have to have their way as long as they have had an opportunity to voice their opinion and have it discussed. He believes this makes an individual more readily able to accept the conclusion of the team.

We continue through the prioritised list of cards, estimating until we have completed the list or completed enough to fill the upcoming sprint.

To understand how many “perfect developer days” will exist within the next sprint, we do the following per individual:

- How many days are they in work?

- How much distraction is BAU (Business As Usual) likely to be?

- Is there likely to be a system test and how long to leave for that?

- Is there likely to be a release and how long to leave for that?

For BAU we take a number of factors into account. Primarily we look at the previous few weeks and guess if we feel our BAU is likely increase, decrease or stay the same. Secondarily we consider any upcoming releases. Should a release be reasonably complex then we would allow extra BAU time to deal with the increase in questions or potential problems.

From this we should have how many “perfect developer days” we have in our 2 week sprint. This allows us, with the card estimates, to fill the available time with the highest priority cards.

We move the cards into our “next sprint” column within Trello and send a confirmation email out to the business. The email confirms out to the business what we are intending to develop so that they can plan appropriately round that.

We do both the prioritisation and estimation process a good few days before the start of the two week development sprint (we will be coming to the tail end of the preceding sprint). This allows us to provide a control mechanism to ensure that the wider business is both aware and understand the content on the sprint. This control mechanism allows us, although very rarely used, to amend or even restart the sprint planning if business priorities require it.

During the development sprint

We first copy the cards from our next sprint column to our current sprint column. This means that the development team are free to start work on the cards.

An individual developer will pick up cards from the top of the current sprint card, move it over to the dev column and start work on it. The developer takes responsibility not just for the actual development, but also progressing the card all the way through to “done”.

Our current definition of done is that the card:

- Has been developed

- Has been peer reviewed by another developer

- Has been reviewed by the originator

- Is ready for deployment

So this makes the developer responsible for engaging with the originator to ensure that the work is understood, developing the solution, coordinate peer review with a fellow developer and sign off by the originator.

Stand up

Each day of the sprint, we hold a morning stand up where the development team talk about the work done the previous day, what work they intend on doing that day and any impediments to that work. This short meeting is held in front of a large TV with our Trello board so that the relevant cards can be referred to.

We have welcomed other departments to take part within our stand up meetings. This has proved great for cross-department buy-in as they see where the development work is and how it effects their plans.

We welcome any quick questions from those departments as well. Occasionally this can escalate into disruptive distracting conversations which would be better served by a separate meeting – however this is rare and we find that the transparency afforded by these quick questions greatly outweighs the occasional distraction.

And then …

We repeat the whole process. Each two week sprint is back to back, with the Prioritisation & Estimation meetings being performed just in advance of each fresh sprint.

Challenge Summary

A quick summary of the challenges and how we address them:

1) How do we engage the intrinsic motivators? To engage the intrinsic motivators we provide autonomy, time and purpose.

Autonomy is provided through allowing the development team how to do the work. It is left to individual developer how to approach the work and select a solution.

Time is provided through allowing the development team to estimate the work rather than impose deadlines.

Purpose is provided through a clear understanding of why something is being asked for. With the developer working directly with the originator to define the work they get a better understand of the value to the end user – making it much easier to buy into the work – thus providing purpose.

2) How do we ensure that we are developing the right thing? By using the two week sprint cycle we are always reflecting on what is the right thing to develop. Our prioritisation process forces us to look at the new cards on the table and pick the highest priority for that point in time.

As time moves on, a high priority card may not continue to be so, thus at worst we are two weeks out of date.

The additional control mechanism of communicating the sprint content a few days in advance increases the processes transparency and allows for adjustment if needed (rare).

3) How do we ensure quality? Quality comes from a number of parts of the process.

We allow the development team time to do the work correctly. By providing a focus on what is “done” rather than an arbitrary deadline. We are not forcing a dysfunctional time vs. quality trade-off.

The peer review and originator review provide early feedback on any quality problems.

Any bugs are dealt with by the development team. Thus they will focus on folding back in any fixes as soon as possible to continue to allow maximum time for development.

4) How do we ensure that we are developing it at the right time? Again this comes down to the two week sprint and the prioritisation process.

At no point in the process are we generally any further away than two weeks from starting work on a new idea. In pretty much all cases this is (and should be) an acceptable lead time for development to start.

A change may come in that demands more immediate attention, but they are generally very rare.

5) How do we ensure that we are developing only what’s needed? This is handled through a combination of the estimation meeting, originator conversations and peer review. All of these should identify quickly if an individual is planning on producing more than requested.

Also by working on two weeks sprints, it pushes the business to break large projects down and focus on the highest ROI activities first. As the sprints deliver portions of the wider project, the business should be able to establish value earlier.

Sometimes this will also highlight ideas that seemed great at the project inception, but as more is learnt, they are found to be of limited value.

6) How do we allow development to start without documentation? The process expects no documentation. Open collaborative conversations with the originator ensure that the developer knows what work is to be done without the need for documentation.

It is critical that the originator remains available during the sprint.

Within our own team, we have found that collaboration works best when the originator is within the same office as the developer as it allows for rapid focused conversations.

When the originator is either unavailable or on another site, it is easy to see that momentum is not the same. Email chains and conference calls are no substitute for the efficiency and team working coming from asking something across the office.

7) How do we maintain momentum? By having a two week sprint, we are always refocusing the team every two weeks. This way we avoid the stagnation that can occur in long running projects.

Energy is kept up with feedback of the work going live very quickly (generally within those two weeks) so the benefits of the work can be seen and discussed.

By seeing the results of their work, this also works towards providing the developer the purpose I discussed in 1) How do we engage the intrinsic motivators?

8) How do we handle change? The Scrum process expects change, thus allows for it.

The original card is purely a conversation marker – thus in itself has little to change. The conversation with the originator will help flesh out the work. And because conversation is encouraged it does allow for some change.

If a card changes fundamentally during the sprint, then we generally have time to adjust. If not, then we ask for an additional card to go into future sprints to handle it.

9) How do we ensure the work is understood by the entire team? By using the estimation process we highlight any differences of opinion – this generally ensures that the team all have the same understanding of the work.

As the work progresses, conversations (such as through the daily stand up) keep the team aligned.

10) How do we ensure we are working together? The onus is on the team to commit to the sprint – this isn’t just the development team, but the wider business.

Everyone knows we have two weeks to do the work – a fairly narrow time box – which automatically focuses efforts to getting it done.

We have seen when teams are not coordinating their work with the sprint then delays and bottlenecks quickly develop.

11) How do we ensure ongoing quality? The developers are responsible for the support and maintenance of the systems – thus to maximise development time, have the motivation to ensure quality is maintained going forwards.

It is well understood by the development team that fixing a problems as early as possible reduces the overall work.

12) How do we minimize project overhead? The process expects no documentation or large project meetings. The focus is on conversation and a joint collaborative understanding.

For example, compared to something like Waterfall, Scrum avoid spending time on producing plans (which are invariably inaccurate) and then spending considerable effort maintaining the plan against actual work.

13) How do we highlight and avoid technical debt? The estimations, peer review and support processes provide a good means of highlighting technical debt.

It is then a team decision if that technical debt is accepted or resolved.

14) How do we expose something is wrong quickly? By keep everything small and focused, very little has the opportunity to be exposed slowly.

Any technical problem can be generally picked up through the daily stand up, peer review or originator review.

In instances where we want to experiment with change (for example to the website), then the two week sprint allows us exercise that experiment quickly and act on its results.

15) How can we ensure that our systems interact properly? By working as a collaborative team and using peer review we can quickly identify any interaction problems.

16) How do we ensure a developer doesn’t become a single point of failure? Again, as part of being in a collaborative team we ensure that the knowledge is retained by the team rather than one individual.

The estimation process and peer review ensure that we are sharing ideas.

Further reading

Drive by Daniel H. Pink During the book, Daniel talks about the development of human motivation. Starting with the basic motivations to survive and reproduce, then into the motivations of reward and punishment and finally into internal motivations. Daniel challenges traditional management techniques based around the reward/ punishment. He provides a body of evidence that, to achieve the best results, we should be using management techniques that allow for the internal motivators to take hold.

Radical Management by Stephen Denning Stephen talks about traditional “command and control” management and how it falls short in the 21st century. Stephen introduces a number of radical management techniques to get the best from today’s works force. Along the way, Stephen talks about many of the principles behind the Scrum methodology but from the perspective of an entire organisation.

The Five Dysfunctions of a Team by Patrick Lencioni Patrick tells us a tale of a fictional executive team failing to work in a cohesive manner. The story first takes the team through the revelation of their dysfunctions to how they resolve them to a successful conclusion. The story is then backed up with practical advice and guidance.

Measuring and managing performance in organizations by Robert D. Austin Robert talks about how the individual targets that we have known and used for many years produce dysfunctional results. Through the book he talks about long established practices and how they don’t work the way we expect.

Conclusion

This series of articles has been an introduction to how we use Scrum and why it works for us.

In future articles I’ll likely do a deeper dive on some of the subjects.