These articles are aimed at senior management funding Software Developer or IT Professionals attempting to show the ROI benefits of what can sometimes seem counterintuitive.

This ever growing library is provided free of charge and can be found here.

In this article, part of my series explaining better ROI from software development, I’d like to look at testing

What is testing

“Software testing is an investigation conducted to provide stakeholders with information about the quality of the product or service under test. Software testing can also provide an objective, independent view of the software to allow the business to appreciate and understand the risks of software implementation. Test techniques include the process of executing a program or application with the intent of finding software bugs (errors or other defects).” Wikipedia

From an ROI perspective, testing should be focused on minimising the financial impact of software not operating as expected.

“Not operating as expected” is a very subjective term and I use that on purpose. How software is expected to behave is entirely based on our own context.

Software crashing would be viewed as all as a bug.

But a “left swipe” on a mobile app not clearing a message maybe unexpected to a user – but had never been intended by the product team.

Testing is about highlighting anything that would be unexpected to the organisation as soon as possible. It is then up to the organisation to decide how to handle that.

Why test

Software development is complex & complicated.

Sometimes even the simplest change can feel like a game of Kerplunk

You pull on the wrong thread and you may have unexpected effects elsewhere in the system. And while in Kerplunk you can see this by the deluge of marbles – in software it can be much more subtle – many times going unseen by the developer.

Testing is there to spot those effects as cost effectively as possible.

For an unexpected effect, it becomes more expensive to an organisation the long it exists. I've talked about this before, but in short it is obviously cheapest to be handled by the developer at the time they add it – and most expensive when it makes it into the wild and affecting your commercial relationship with customers.

So ideally we want to resolve as early as possible.

You then need to think about the investment to find it.

You could employ a massive QA (Quality Assurance) team to test and validate everything you do.

But is that cost effective if you are making very small changes to an internal website with no critical impact if it goes wrong?

Unfortunately there is no one-size-fits-all rule for testing. It will be different per organisation based on risk and cost.

Methods of testing

There is a considerable body of research into testing. There are countless books, courses, articles, etc devotes to the subject.

So … no plans for me to go through them all in this article.

For this article, I wanted to look at 4 types – manual, unit, integration and acceptance.

Manual Testing

"Some say he appears on high-value stamps in Sweden, and that he is wanted by the CIA. All we know is, he's called The Stig" - Jeremy Clarkson, Top Gear presenter

Like Top Gears tame racing driver, our manual tester should be putting the software through its paces. Pushing it to its extremes and likely taking it places that hasn't originally been intended.

I suspect very few car designers started with the premise of designing their car to be thrown around an airfield by the iconic anonymous driver.

And that is where testers takes our software.

Or at least they should do.

Too often “the Stig’s software testing cousin” is spending their time doing repetitive, same well trodden path style testing. This is where most testing practice starts. Create a list of tests, and pass them over to someone to repeat over and over again.

Those test will generally be your core operations – so will be great for making sure that that well trodden path works – but it does very little for anything that detours off that path.

What we should be using our tester for is designing tests that can be automated. Testers define the test – the developers automate it – the tester moves onto the next set of tests.

Once automated those tests can run by the system. You can run those over the weekend, at night, during lunch, etc – you aren't constrained to the individual.

This should be freeing the tester up to find those less trodden paths through the system. Ultimately improving the quality of the software and thus the ROI.

Automated Unit Testing

One of the most common types of testing produced by developers are unit tests.

When I say produced – these are software in their own right. They are like mini-programs that validate the lowest level component in the software.

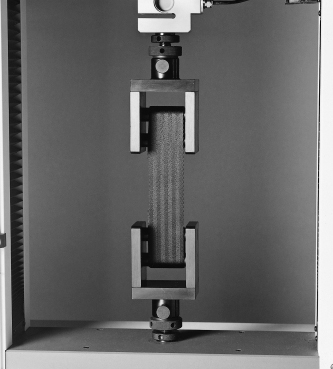

Image you have a car. Unit testing would be looking at one component of that car and testing it to prove it operates as expected.

Take the seat belt material for example. When buying you car, it really isn't a consideration. But the amount of testing that goes into that single component of the car is phenomenal.

And do you think that the material is tested by hand?

Nope. They automated the process with a machine.

While I expect it is expensive to setup the machine, once that machine exists then it can be used to test different samples of material very cost effectively.

This is the same principal as Unit Tests in software development.

In most cases (unless you are deeply technical) you are unlikely to get involved or care about the Unit Tests – other than they exist and are being used. As with any test, if they are not maintained in line with the system under tests then they quickly lose value.

It is key that a development team are empowered to produce and maintain those Unit Tests. And when one fails then the team need to understand why. Was it because of a desired change in the system (and thus the test needs to be updated) or was it unexpected due to something changing elsewhere?

Setup right those Unit Tests can provide exceptionally fast feedback to a developer (within minutes). This reduces the impact of any problem greatly because recent work is within the developers mind, thus (in theory) making it easy to find the source of the problem. And of course then fix as appropriate.

Automated Integration Testing

Automated Integration Tests are similar to Unit tests, but will tests how well a number of components work together.

In our car example, we’d want to perform integration tests against the engine.

We can test all the components of the engine work correctly in isolation – but we need to test them in the aggregate to ensure that our engine is doing what is expected.

Again these are generally tests for the immediate benefit of the development team.

Automated Acceptance Tests

Acceptance tests are the part that you are getting involved.

Acceptance tests should be the key characteristics of the software and should be an agreement between the business stakeholder, the tester and the development team.

They should be at a high level of granularity – so for example, we want to make sure that the car starts, drives forwards & stops (along with making sure the radio works).

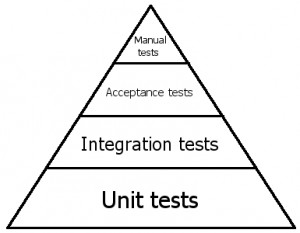

The quantity of these will depend on your individual circumstances, but the testing triangle should give you an idea:

Working down the triangle, you should have:

- More Acceptance Tests than Manual

- More Integration Tests than Acceptance

- More Unit Tests than Integration

The cost to create and maintain the tests are in line with the quantity you should have. Unit tests are considerably cheaper and easier to maintain that Acceptance tests.

Importance to you

As I've said above, as a business stakeholder, the Acceptance Tests should be of greatest importance.

Yes you should be confident that your development team are creating Unit & Integration tests – but unless you are technical, I’d keep out of the details.

The Acceptance Tests however, in my opinion, should be written in such a way that they require no technical expertise.

These tests should be what you as a business are signing off on. These are the key aspects that prove that the software does what you need it to do.

If you can’t understand it, then how can you possibly do that?

The key here is that the tests should be written in plain English (or relevant language). Test results should also be provided using that same plain English.

How that is accomplished is up to your development team.

I personally like to use a tool called Specflow. Here is an example of an Acceptance Test for a calculator application:

- Given I have entered 50 into the calculator

- And I have also entered 70 into the calculator

- When I press add

- Then the result should be 120 in the screen

This doesn't need any technical expertise to read and understand.

So if this can be read and understood by the business, it has inherently more value. It means that it is clear to a wider community what is being tested and how. By enabling this, the more likely the test is correct and current.

Much less susceptible to miscommunication between the development team and the business because they are using the same language.

ROI Summary

Good testing makes for good productivity and a quality product – all great stuff for ROI.

There will always be a tipping point between effort and reward (in all things) – but when doing that assessment, take into account the potential lifetime of the product (3 – 5 years generally).

The key is to ensure that your team have the time and empowerment to implement AND maintain the proper testing. It will always be tempting to cut corners when the pressure is on – but if you don’t do it right now, when will you?