These articles are aimed at senior management funding Software Developer or IT Professionals attempting to show the ROI benefits of what can sometimes seem counterintuitive.

This ever growing library is provided free of charge and can be found here.

In this article, part of my series explaining better ROI from software development, I’d like to share my thoughts on Dependencies. This is the first of three articles in this mini-series.

Overview

Dependencies in any project are expensive. They are introducing a hidden tax on our projects.

Dependencies maybe due to inter-team communications.

Dependencies maybe due to complex inter-reliant systems.

In short, reducing those dependencies will reducing those hidden taxes.

Standing on the shoulder of giants

These articles build on the concepts I’ve previously introduced when talking about Agile, Scrum and progressive companies such as Spotify and Facebook. You don’t need to have read those in advance, but I’ll include relevant links at the end of the dependencies mini-series.

The Acme Corporation

For this mini-series, I wanted to take a different approach. I wanted to express this more as a story. The story of fictional company as it attempts to improve its return on investment by reducing expensive dependencies.

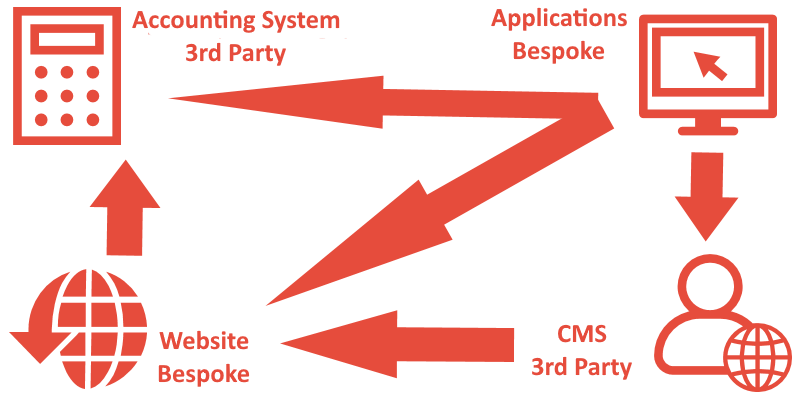

Let’s take the Acme Corporation. It’s a SME with a fairly generic set of systems:

- 3rd party CMS

- 3rd party Account system

- Bespoke website

- Bespoke apps

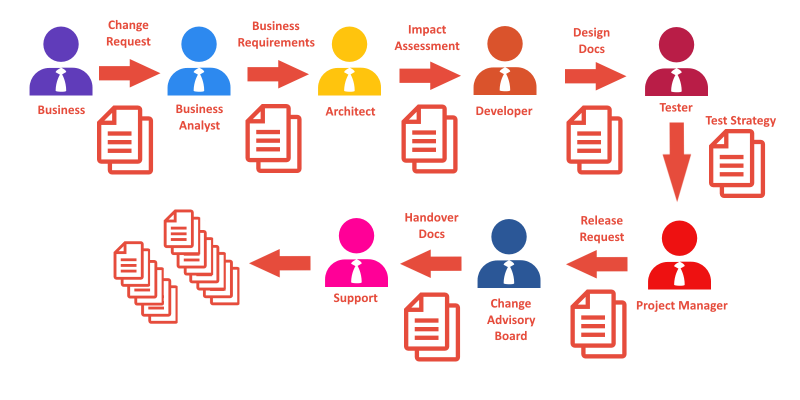

Their development pipeline is what I’d consider fairly traditional;

The development pipeline follow an idea from concept to realisation. The idea will move from department to department – generally with supporting documentation.

The Ache Corporate is headed up by Ed (CEO)

Fiona is the CTO

They have recently had a management consultancy review their operation – the output of that review highlighted a number of opportunities:

- Lots of wasted documentation. Most are transient. They are being used for the course of the project only - thus have a very short life (and thus value)

- Considerable elapsed time between departments. This is time that isn’t adding value to the project and also has an impact on the timeliness (and thus value)

- Considerable effort to coordinate a release across departments. Acme expect every change to be documented in detail and reviewed/ approved by all departments. This results in considerable coordination effort and delay

- Clear evidence of status-quo resulting in dysfunctional behaviour – long release cycles leading to batching of changes leading to larger change leading to longer release cycles

- Different systems and parallel projects are causing a lot of jumping between priorities in the working day. This is leading to lost efficiency while team mentally switch between projects and has a high cost in mistakes due to confusion.

Ed meets with Fiona to discuss the findings. He sees the opportunities as a great way to propel the Acme Corporation forward – but has concerns.

“How can these opportunities be realised while still getting the right thing and not putting the business at massive risk?”

Fiona commits to sit down with her team and come back with a proposal.

Removing those dependencies

Fiona scheduled a number of workshops with her team and they soon identify that benefits could be gained from removing as many dependencies as possible.

They realised that the key was to reduce the number of times a conversation needs to go outside of a team.

Designing the team

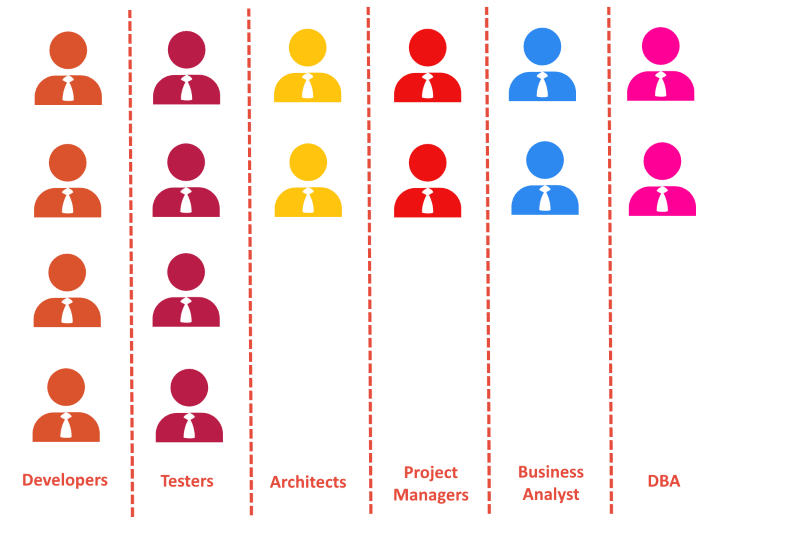

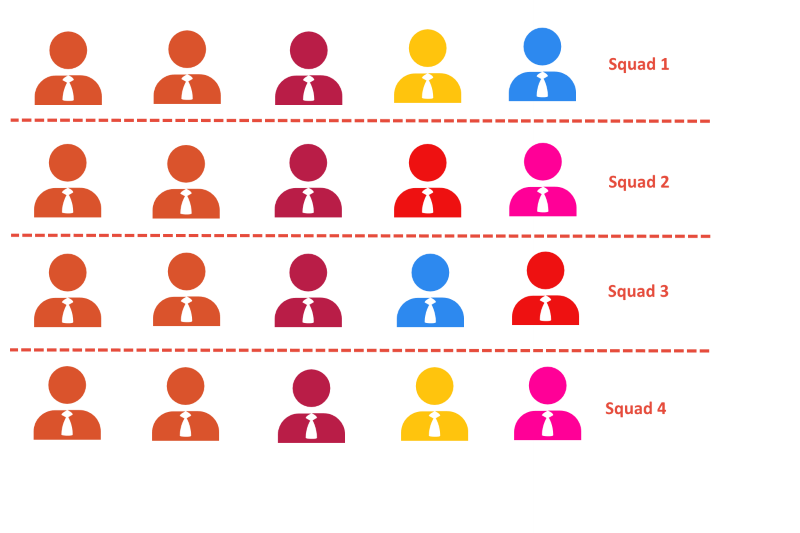

The first thing they looked at was how the teams were structured.

Collectively, they arrive at the following team guidelines:

- A team should have responsibility for the system(s) from “cradle to grave”

- A team should have enough skills to minimise dependencies when taking a change from idea to realisation

- A team should be no greater than 9 people to minimize engagement overhead

- A team should have a size appropriate for the system(s) they are responsible for

With the guidelines in place, they agree that the team should be responsible for not just the project delivery, but also the day-to-day support. They all agree that when a team supports a system, they are motivated to make sure that the system works really, really well.

They look at their current team structure:

And they agree on a squad based structure – focused around the products. The squads where to be designed to meet the guidelines they had agreed upon.

Trialling the team

After further thought, Fiona wanted to provide a concrete example for Ed – an example that she’d want to trial.

So she sat down with the team again and asked their opinions on where to start with a trial.

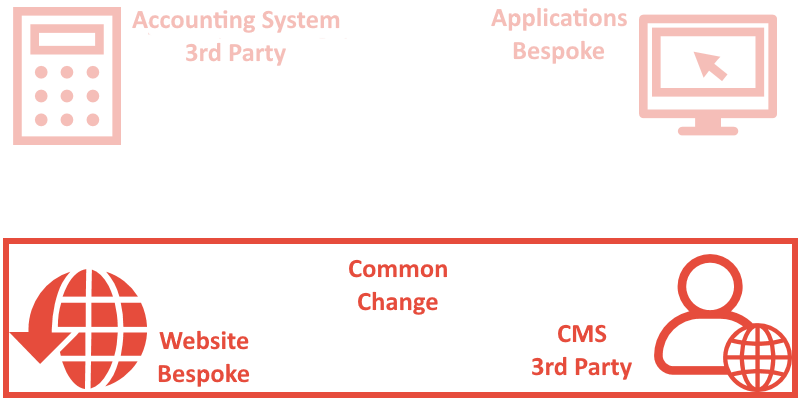

It was agreed to start with a single squad. And to look for an important system that squad could own.

They didn’t want to use an unimportant system – there was little wow factor in that. And to make a meaningful change they knew they would need a wow factor.

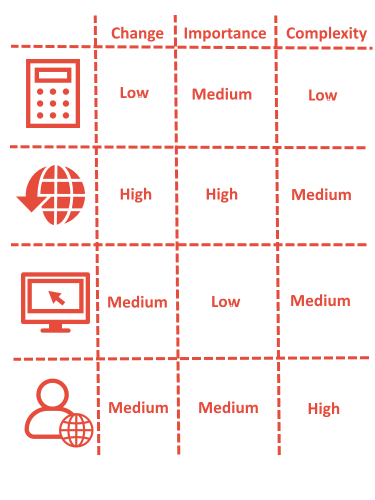

They looked at the systems based on the volume of change, importance and how painful it was to get changes. They arrived at a simple matrix:

After review, they found that the website and CMS where pretty much always changed together, changed regularly, and where a fairly painful event every time they changed. If the end to end change process could be improved, it would represent a real game changer for Acme.

Building the squad

Having identified the systems and they turned to defining the squad what would be needed to manage it.

They look at the historical and planned changes for the systems to gauge what sorts of skills would be needed. After some analysis they arrived at their squad structure.

Defining the Process

To provide the squad with focus they went further and defined some rules.

They collocated the squad in a separate office – in which they could work together easily, but also minimize distractions.

The squad would be expected to deliver change every two weeks into production. They would be responsible for the quality of the software they released.

They should be coached to focus on small, discrete changes – actively minimising dependencies.

The squad would be responsible for agreeing what could be accomplished within the two weeks, planning, developing, testing and implementing it. At all time the responsibility would be with the squad as a whole.

Objection Handling

In their final workshop, Fiona and team went through concerns they had about the trial.

They felt that the biggest blocker to success was buy-in from all of the stakeholders. While the trial would have top level approval – without full organisation engagement, they could easily see the squad members being distracted by their old job.

They decided to prepare a town hall style meeting open to all.

Next time

In the next article, we’ll follow Fiona and team as they handle questions from the wider organisation.